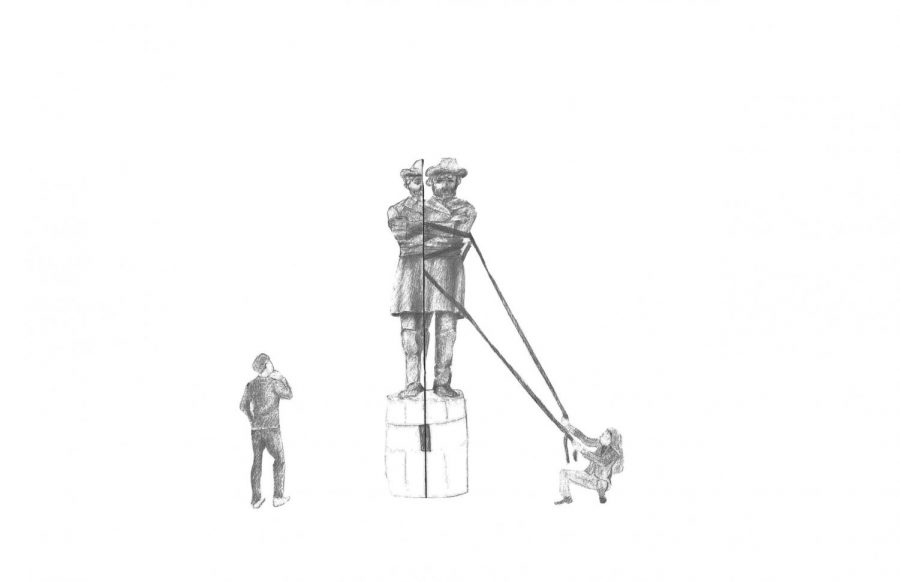

Credit: Illustration by Katherine Lee

Two Words on Civil Unrest

Should statues of Confederate leaders be removed from public spaces?

November 9, 2017

No

At first glance, the issue of whether or not to take down Confederate monuments seems relatively straightforward when viewed from a 21st century perspective. Fighting a war to preserve slavery is not something that should be honored, and thus the statues and monuments that honor the Confederacy should be taken down. While this may be is true in some cases, in many cases the issue is not that simple.

While it is true that as a whole, the Confederacy’s secession from the United States was primarily motivated by the desire to preserve the institution of slavery, the motives of individuals were often more complicated due to factors such as loyalty to one’s state and the aggressive tactics employed by Northern generals such as William T. Sherman. For these reasons monuments like the one in Durham, NC dedicated “In memory of the boys who wore the gray” and statues of Robert E. Lee should not be removed.

The Durham monument is a prime example of a statue honoring Confederate soldiers that should not be taken down. Even in the Confederacy, over two-thirds of the population did not own slaves, and thus it would be an oversimplification to say that most of these individual soldiers were fighting to preserve slavery.

In addition to fighting out of loyalty to their state, these soldiers were often fighting while their state was being invaded and in many cases were fighting to protect their property and land. Many of the battles of the Civil War were fought in southern states, and in many of these battles, towards the end of the war generals like William T. Sherman used “scorched earth” tactics of burning and destroying property as they took cities. These tactics were clearly justified as necessary steps towards winning the war and ending slavery, but they also make it hard to blame average civilians for not sitting by as their towns were destroyed. This is not to say that these soldiers were entirely innocent—they did contribute to a war that was fought to preserve slavery—but it is not wrong to memorialize people who fought and died to save their towns from being destroyed. Individual confederate soldiers did not chose to secede from the union, and fighting when one’s state is being invaded and in many cases being attacked using scorched earth tactics is very different from fighting to preserve slavery

Although Robert E. Lee cannot be seen to be as innocent as individual confederate soldiers since he was a general of the Confederate army, his character and motivations were complex enough to justify leaving monuments dedicated to him standing. Lee’s views on race would be considered backwards and racist by modern standards, but it is easier to understand why he held these views considering the environment in which he was raised.

For someone who was born in 1807 and raised in the 19th century South, his views were hardly unusual and if anything relatively progressive. Although he did not support abolition, Lee was opposed to slavery, which he called a “moral and political evil.” As stated previously, Lee did hold views on race that were obviously racist, but he did recognize the evils of the institution of slavery, which is more than can be said about many people at that time. Additionally, Lee said, “If Virginia stands by the old Union, so will I. But if she secedes (though I do not believe in secession as a constitutional right, nor that there is sufficient cause for revolution), then I will follow my native State with my sword, and, if need be, with my life.” Clearly, Lee was more motivated by an unwillingness to betray his state and fight against his home than to preserve slavery, and was even against Virginia’s secession in the first place. While these factors do not completely justify Lee’s actions, they do make his character much more complex than other Confederate leaders like Jefferson Davis.

For these reasons, considering whether or not to take down statues of more complicated figures like Robert E. Lee and “the boys who wore the gray” is very different from the decision of whether to take down statues of other Confederate leaders like Jefferson Davis, who overtly supported slavery. There is a much better case for taking down statues of figures like Davis, but monuments like the one in Durham, NC and ones dedicated to Robert E. Lee are not worthy of being taken down because of the complex nature of the people that they honor.

Yes

With statues of Confederate generals such as Robert E. Lee being relocated from public spaces to museums and protests-turned-riots breaking out in their wake, the question of keeping or relocating these statues has come to the forefront of today’s political discourse. While these statues ought to be relocated from public landmark sights to the contextual and didactic environment of museums, one must first understand the context of their construction.

The majority of statues glorifying the Civil War and Confederate generals in the American South were constructed in the late 1800’s, after the end of the war and Reconstruction. They were built in a fervour now called “the Cult of the Lost Cause,” which actively sought to rewrite the narrative of American history. Its proponents argued that the war was a heroic one for the Confederates, that they were not rebels defending an inhumane institution, but rather loyal soldiers and generals who sought to protect Southern ideals, people, and rights from Northern oppression.

Republican advocates for preserving the statues point out that the majority of Southerners did not own slaves as proof that slavery was not the focus of the war, instead suggesting it was an issue of preserving Southern autonomy and states’ rights; this is an oversimplification.

Despite that one statistic, it is a general historical consensus that the Southern economy was wholly dependent on slave labor, for both tobacco and cotton. In 1861 Vice President of the Confederacy Alexander Stephens explained, “[the Confederacy]’s cornerstone lies upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man. That slavery is his natural and normal condition.”

To claim that any general including Robert E. Lee was not defending slavery would be counterfactual. Robert E. Lee and his comrades all owned slaves, and were well aware of the fact that their war was one that sought to protect slavery. These generals, regardless of their personal morals, fought to preserve the short-lived Confederacy and its slave-based economy. Thus the moral narrative that these statues embody is one of revisionist history.

These statues erase the history of people of color in the South. While streets are laden with statues of these generals and men who fought for a cause of oppression, their glorification and commemoration gives little mention to the 15 million slaves who died in the Slave Trade and the antebellum plantations. Regardless of the personal opinions of any of the people displayed, they did not choose to have their statues built; they were made by “Lost Causers” who specifically sought to rewrite the history of the South to ignore its atrocities and paint an elegiac light on the Confederacy.

In the words of New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu, who oversaw the removal of a statue of General Lee in May, “These statues are not just stone and metal. They are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictional, sanitized Confederacy; ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, and the terror that it actually stood for.”

By existing on display as monuments in the public eye, these statues demonstrate both approval and glorification of their narrative, which is one of whitewashing and a willful ignorance of the suffering of millions of African Americans for which these men fought and on which they relied.

Yet these statues’ racist histories do not diminish their historical significance. As is planned for the Jefferson Davis monument formerly in New Orleans, the Confederate statues should be relocated to museums, where they can be displayed alongside the full context of the underrepresented darker side of the Civil War and the South, and understood as pieces of ideological propaganda from the “Lost Cause” movement. These statues are historically important and worthy of remembrance; however, we should move on from the bygone era when public endorsement of white supremacy was acceptable. The Confederate statues belong in museums, not public parks.