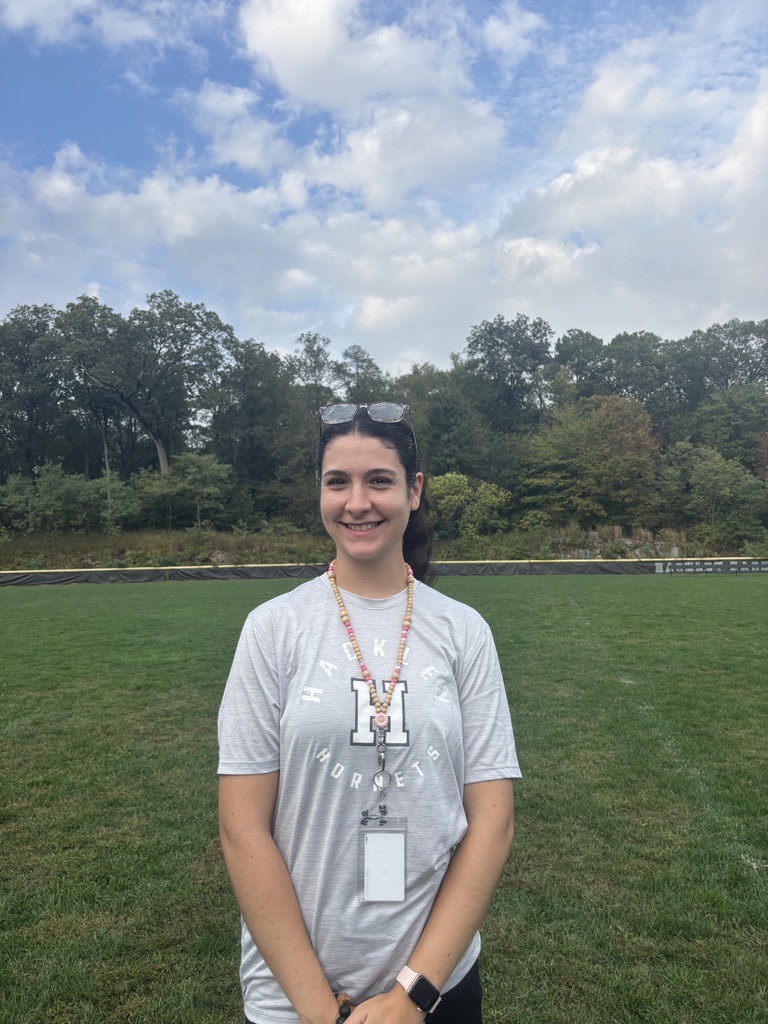

Scheduling is a game with hundreds of moving parts. It’s like playing 3D Tetris. Hackley’s registrar, Bess Seewald, who creates all the teachers’ and students’ schedules, describes her job as a task “to facilitate teaching and learning on the logistics level.”

“The take-home message for students is, be very specific with your advisor about your choice and what your priorities are,” Ms. Seewald said.

This small act is extremely beneficial with the “3D Tetris” that is the scheduling process.

The first pieces are set during the winter, when department chairs and the leadership team begin to brainstorm the courses needed for the next year.

“The winter is spent figuring out what courses are needed based on what students are taking now and what they anticipate will be needed to fulfill course requirements for the following year,” Ms. Seewald said.

From midterms to after spring break is when the challenge begins to intensify. By that time, the course catalog will have been edited so that students get access to it. They hear from their deans and advisors about what they should be doing to fulfill their requirements, and also plot out their four-year sequence.

When course selection ensues, Ms. Seewald once again stresses the importance of writing notes when making choices. She cannot read minds, and does not always know which classes matter most.

“Sometimes, from experience, I can kind of use my judgment,” she said, “It’s much better if I don’t have to guess.”

Some examples of what notes can be beneficial to Ms. Seewald can include writing notes on which of two minors is most important for you to receive, or if you requested to be in two minors, give three minors that you would equally enjoy.

“Summer is when the whole puzzle starts to come together,” Ms. Seewald said.

Ms. Seewald first starts with the middle schoolers’ schedules. This is a different challenge from scheduling the upper school because, unlike the upper school, middle schoolers do not have free periods.

“I have no flexibility there; every single period has to be filled,” said Ms. Seewald.

She has to make everything fit into place. Ensuring that she groups the math and the language classes so that every child has a place to go when there’s math and a language.

“I have to reconcile the fact that the way teaching and learning happens in the middle school, optimally, is different then the way teaching and learning, ideally, happens in the upper school.”

Ms. Seewald aims to have the middle school schedules completed during June, so she can use their schedules as a base for crossover teachers, teachers who teach both in the middle and upper school.

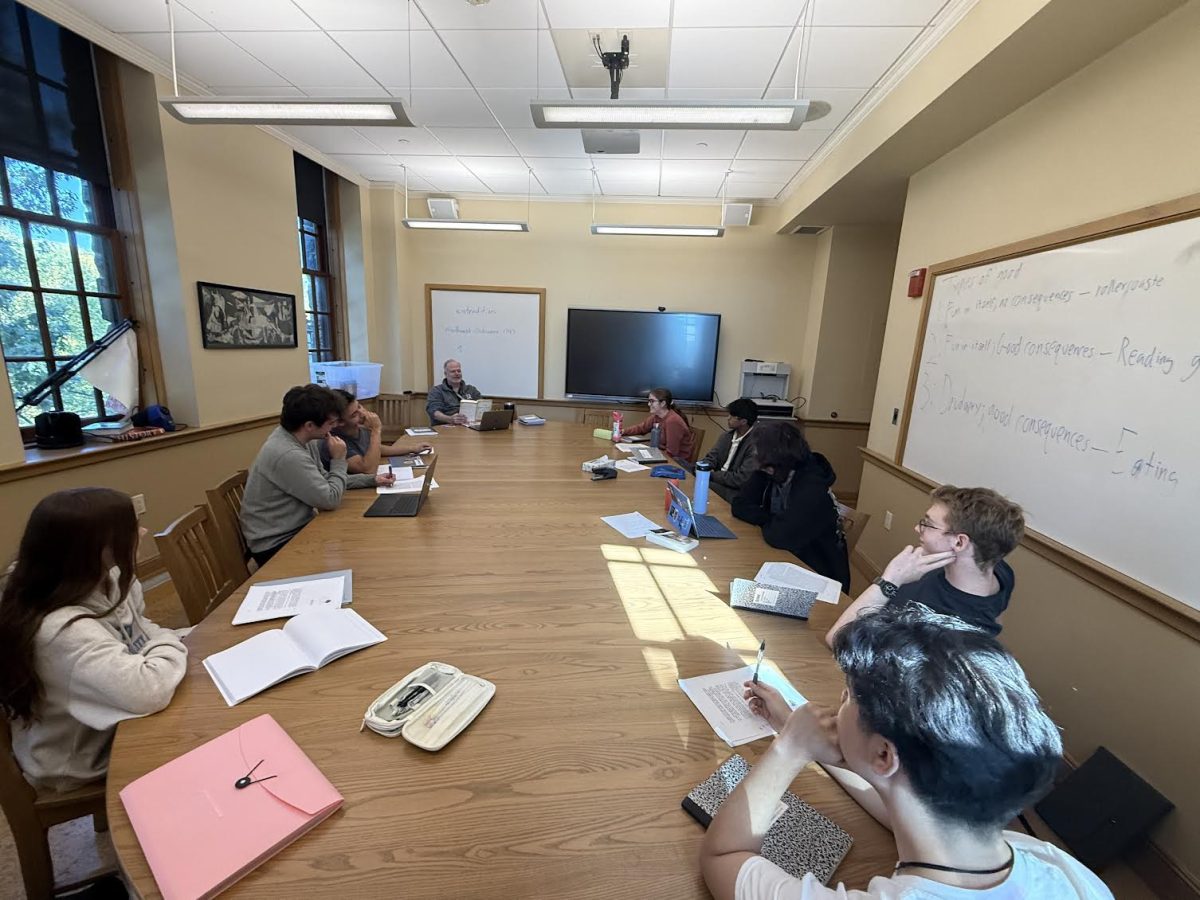

New classics teacher, Benjamin Driver, who teaches in both the middle and upper school, serves as an example to show how complicated scheduling these teachers can be.

“Mr. Driver teaches five sections. When I plan his classes, I deliberately back-to-back his middle school classes because by having them consecutively, that minimizes the number of crossover conflicts,” Ms. Seewald said.

She uses a complex guide to help her with scheduling these teachers.

“This guide is crazy and would take some time to explain,” Ms. Seewald said.

Once she has the crossover conflict teacher’s schedules set, she finally begins working on the upper school students’ schedules. From this point, it is a sprint to complete the puzzle. Her main priority for high school is to get everybody into as many of their top choices as possible. This can be hard when so many students switch in and out of their selected courses. Just this year, from May to late September, 254 dropped and added classes came into her office.

“I might spend, you know, a couple of hours working really hard to get a student into a class, and then I get an email saying they’re [switching out],” Ms. Seewald says, “That’s kind of par for the course.”

Some switches do have drawbacks, and Ms. Seewald makes sure to highlight them when communicating with the student.

“If it’s an easy swap, I just do it, but if it can have ramifications, I let them know,” Ms. Seewald said. “If it is more time sensitive, the student will be on [the email]. If it is not a really big rush, I’ll just [email] through the advisor.”

These are the type of tiny decisions she has to make daily when it comes to students’ schedules.

One of the hardest pieces to fit in the puzzle is scheduling seniors and juniors taking classes with only one section. Ms. Seewald names these classes “singletons.” She explains that it is imperative that she gets upperclassmen into the “singleton” classes because it could affect specific students’ graduation requirements. This idea is communicated to the seniors by Brigid Moriarty, the head of the English department.

“Ms. Moriarty explains to the seniors, these [singleton classes] get prioritized and then English 12, you try and get your first or second choice, but it can’t be guaranteed,” said Ms. Seewald.

When seniors and juniors choose to switch classes, it can be even more damaging to their schedule. One real example, according to Ms. Seewald, is when a student wanted to change from a singleton math class to another class, but in doing so, the student would not be able to get into the English 12 that he requested.

One student whose schedule switch shifted the outcome of his entire year is sophomore Henry Pascual. As a freshman, Henry took two math classes: Geometry and Algebra II. But as time progressed, Henry decided to drop out of his Algebra II class.

Despite how difficult switching some classes can be for Ms. Seewald, she said that it’s okay to change your mind.

“That’s part of being a student, you might try something and it may seem like a reach, and then you realize it’s the challenge that is a little bit much, and you want to switch sections,” Ms. Seewald says.

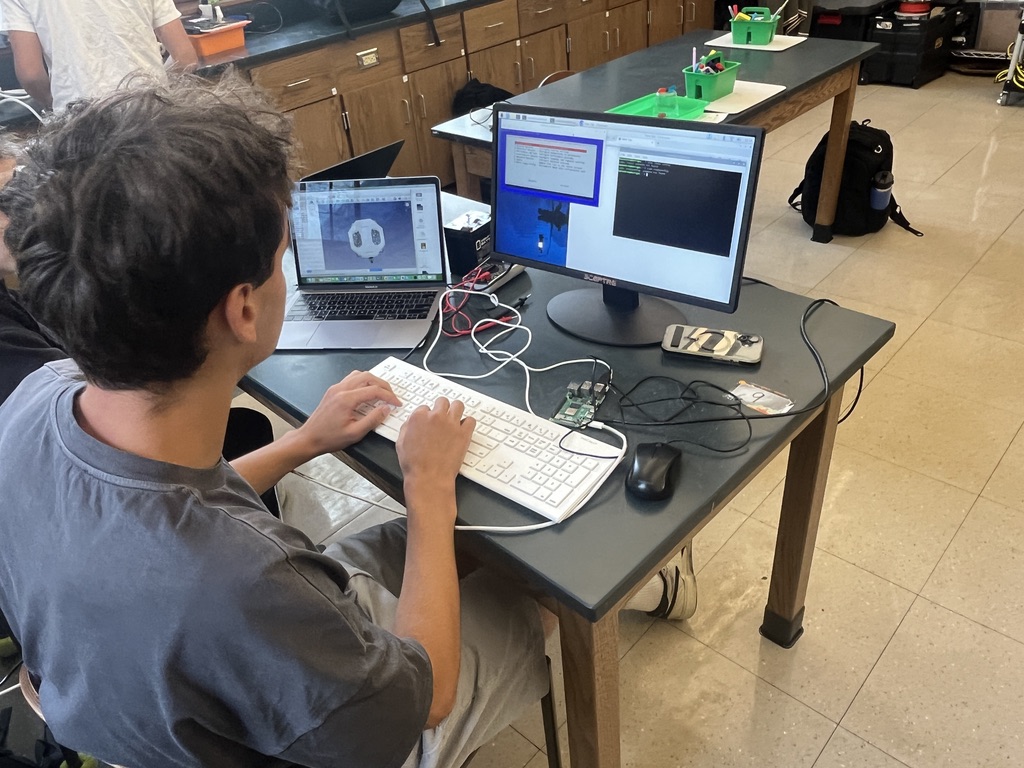

Another student, Isabelle Genden, is taking a sixth major called Independent Science Research Project (ISRP). The choices she made in course selection helped her accommodate the added work that comes with a sixth major.

“Considering I am a sophomore and there is a lot of work, I would keep six majors, but I think next year I might consider adding a minor,” says Isabelle.

This is the type of considerate thinking that can go into student course selection.

Ms. Seewald’s job took years of learning before she was able to accomplish what she does every day. Before becoming a Hackley registrar, Ms. Seewald was a science teacher at Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School, which did not have a formal registrar job. She worked with the math and science teachers to put together schedules. It was part of their responsibilities. Ms. Seewald was able to apply her knowledge as a science teacher to the scheduling responsibilities she has now. Much like being a science teacher, scheduling contains a lot of trial and patience. The one quality Ms. Seewald knows best.

“What I really like about my job is when I can give students and teachers a schedule that really works for them.”