Shining Hope Over Hackley: A Q&A with SHOFCO Co-Founders Kennedy Odede and Jessica Posner

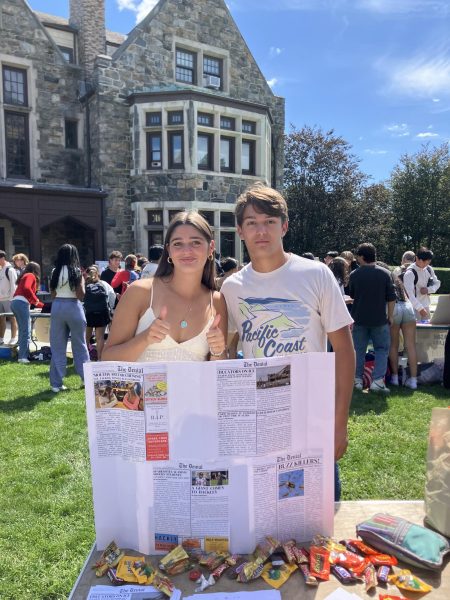

Credit: Alex Meyer

Jessica Posner addresses Upper School students in the 2016 Wendt Lecture.

The Dial had an exclusive interview with SHOFCO co-founders Kennedy Odede and Jessica Posner during their visit to Hackley on Thursday, February 4.

Q: You started SHOFCO at such a young age (15). How did your passion for soccer help start SHOFCO?

Kennedy Odede: I used to be a soccer player. Soccer for me was not just soccer. What I love about soccer is the idea of discipline and teamwork. I got a lot of my leadership things through the idea of soccer. You have to be organized and you cannot do anything alone.

Q: What skills did you learn at Wesleyan that helped you develop SHOFCO?

KO: I think many skills I learned from my life on the street — I call it “Kibera University,” the university of life. I had raw leadership, not organized. I loved Wesleyan because I learned a lot of structure. I learned how to speak. I learned how to write and how to organize your thoughts. So Wesleyan is my core, my foundation, of who I am now. And how to critique, analyze issues. So I think those things, coming from a society where everything is the way you see it — if it is blue, it is blue. Going to Wesleyan you can see something differently. So that is what I loved about Wesleyan.

Q: You discuss your love of reading in your book, and how you’ve you’ve learned from people such as Martin Luther King, Jr. and Marcus Garvey. How have you applied their ideals to your work at SHOFCO?

KO: What I’ve done mostly is follow the ideas of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Marcus Garvey and Rosa Parks. These people became more like a friend in my life (It is weird, I know that) because, as a young person, you need mentors. You need people there for you. And I was alone. So I had this idea of these leaders, and what I really loved about them was selflessness. They were willing to sacrifice a lot. I want my teachers to instill the values that materials are not that important, so they can teach kids if they want to be a doctor or a journalist. I also want them to tie whatever they do back to the fact that whatever people do for humanity is not driven by money. I tell my teachers to tell my students to be open and it’s not all about self-interest. They have to see the bigger picture.

Q: How were you able to put your dehumanizing experiences into words?

KO: That was very, very hard. Some of them I wrote them when I was still fresh from Kenya, when I came to Wesleyan. But honestly Jessica is very good at it; she helped a lot with the flow of the stories. So she takes the credit.

Q: Why did you decide to go back to Kenya after Wesleyan?

KO: You have to understand my past before I talk about my present. I was a young boy who was very tired of society, injustice, and wanted to bring change. I believe you have to bring change by collectivity. For me it was not about getting out; it was about being successful. I thought about what I can do to change my community. So when I got out, I was sure sure I made it. I had a good shower, good food, beautiful girlfriend. Life was good; it was true. So why did I want to go back? You can realize that my mission was not about me. My goal was that we have to change our society. We have to change my community. And I wanted to be an example of how it was a hard life at first, but someone with privileges still wanted to sacrifice everything to go back and show the community that it was not about the individual. If we can all do this together, we can make this community a better place.

Q: What was one of your most memorable moments in Kenya?

KO: I think it was when Jessica got malaria. When she thought she was going to die; that was a little bit scary. You may have killed her, a stranger I didn’t know too well yet. That was really scary.

Q: How has your command of Swahili helped you connect with the people of Kibera?

Jessica Posner: I think it’s always so helpful to understand what’s going on around you. In Kibera, people definitely speak English, but also a lot of Swahili, and so I think that learning Swahili makes people take me a little more seriously. I feel like it’s an investment on my part; that I’ve invested learning the language so that I could communicate. It definitely just helps to be a part of things in a more organic way.

Q: Based on your experiences in Kenya, how has your perception of “community service” or “service learning” changed from the American perception?

JP: Definitely. I think the perception of community service [in the U.S.] can be very one-sided, it’s all about giving to a place, a community or a project in need. What I’ve learned is that I’ve definitely gotten as much, if not more, than I think I have given. I think that sort of reciprocity is so important.

Q: What was one of your most memorable moments during your time in Kenya?

JP: I think it’s still the first day I saw Kibera and feeling so overwhelmed by this place. Kennedy was an hour and the half late to meet me, and I would just keep calling him and he would tell me he’s coming. He shared this place with me; it was so overwhelming and something I couldn’t imagine before. To be both overwhelmed and comfortable was so memorable to me, because Kennedy was guiding, protecting and shepherding me through this experience. At the same time, just seeing so many people, and all these little businesses and all these kids running from these informal schools, (things we would never consider “school”) left a mark on me. That first moment is still really fresh in my mind.

Q: What are your current responsibilities at SHOFCO? What do you do on a day-to-day basis?

JP: I do a lot of the operations– integrating what’s happening in all of Kenya’s programs. I work on the strategy, implementation, and integrating that with our efforts to raise money and spread awareness here. Also, I make sure that the needs of the programs are met.

Q: Where does the title “Find Me Unafraid” come from?

JP: It comes from a poem called Invictus, which was one of Nelson Mandela’s favorite poems. It was a poem that meant a lot to Kennedy as a young person and that he looked for comfort and inspiration. It’s a line from the poem that we felt like it also described the leap that we’ve both taken in different ways, both individually and together.

Q: What advice do you have for students wanting to give back to their communities in a meaningful way?

JP: Start small. It’s easy to feel so overwhelmed by the problems or the challenges, but don’t let that stop you. It can start with 1 person. It can start with doing 1 thing once. You have to start. Also, find people to work with from the community so that you’re not just coming in from the outside and going up, Find a partner and people who are living in the community that you want to work with to help guide you and teach you about what it is that they really need.

Q: How do you envision a grassroots movement such as SHOFCO spreading to other communities and nations, and even to a community such as Hackley?

JP: I think that part of it is the example of the story. Seeing that a 16-year-old kid in the largest slum in Africa can take 20 cents and buy a soccer ball shows you can do something. People can change their own lives. That message is the spark that will start spreading the movement, and that movement can go further – across Kenya, Africa and beyond. It’s sort of a philosophy that people in communities everywhere can be taken and inspired by.

Q: What are your future plans for SHOFCO?

JP: We have big hopes. This year we’re building a new school building, starting satellite health clinics, starting community centers. We’re still taking the infrastructure we started with and expanding and growing it. Beyond that there are hopes to start more communities across Kenya, but perhaps one day move beyond Kenya and to take this model of a girls’ school at the center of holistic services. Just taking that idea we’ve created and spreading it is really important to us.