Alongside four other Upper School students and three teacher chaperones, I traveled to Nairobi, Kenya for the October 2023 Round Square International Conference hosted by Brookhouse Schools. The Brookhouse Schools comprise a private educational institution that teaches with a British Curriculum and is an active member of the Round Square network, which seeks to connect like-minded students from schools around the world.

Students explore one of the many stops taken during a three-hour bus ride out to the Rwandan countryside. Alongside other Round Square delegations, Hackley students crossed a suspension bridge overlooking a river. Student ambassadors Peter Roberts ’25, Fernanda Paz ’25, and Isabella Barriera ’25 tentatively approach the wooden bridge before following peers from a school in Calgary.

Many schools took part in individual post or pre-conference trips with their respective students throughout countries and cities spanning the continent. Hackley’s delegation chose to spend a few days immersed in Rwandan culture, landing in the capital city, Kigali, then taking long bus rides to the outer reaches of the countryside.

Rwanda is known for its high elevation, often referred to by the people as “the land of a thousand hills,” with a geographical landscape dominated by rolling mountains and scattered lakes. Despite landing in Kigali long after dark, the short yet sloping bus ride to the hotel confirmed to me that the nation is indeed “the land of a thousand hills.”

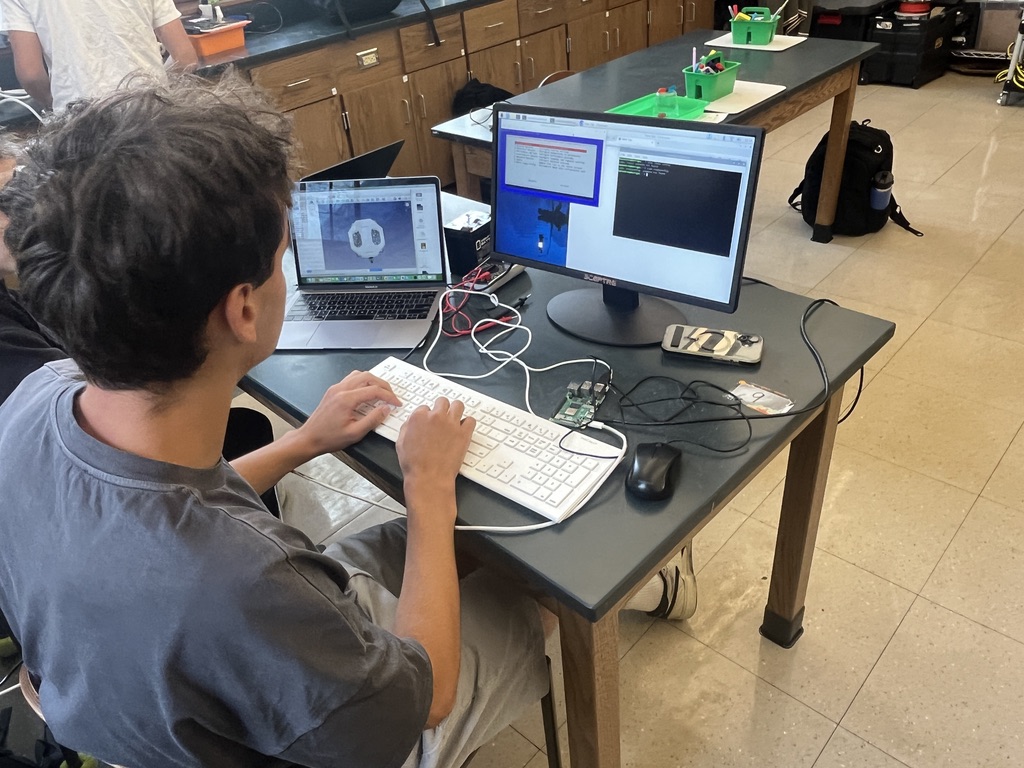

After a delicious dinner of french fries, stew, and popcorn chicken, the delegation enjoyed a night of rest and was up bright and early in the morning for our first adventure in Rwanda. Boarding a bus at seven with a delegation from Calgary, our group enjoyed a scenic, three-hour bus ride to the countryside. Our bus driver and group tour guide even took time to stop at hidden lookout points and suspension bridges so that students could explore, take photos, and stretch their legs.

Throughout the bus ride, I was struck by the immediate contrast between the Rwandan countryside and the bustling streets of Kigali as we drew closer to the outer limits of the city. With such narrow, winding roads, it almost felt as if our large bus was on the very edge of a cliff, constantly crawling higher in elevation as we drove.

Student Ambassadors examine rock formations along the walls of a cave. The cave depicted is one of many that are part of the complex Musanze system. In order to protect themselves from hitting their heads on rocks, students and chaperones wore brightly colored hard hats with flashlights attached.

After what only felt like a short ride, the bus reached its first destination: The Musanze Caves. As one of Rwanda’s most recent and popular additions to a widening array of tourist attractions, the Musanze Caves are a complex system of underground tunnels and caverns filled with rich tribal history.

Centuries ago, Kinyarwandan tribes considered the cave system to be sacred ground upon which to crown new kings. Aside from their history, the caves are also home to thousands of bats, many of which I saw during my group’s two-hour exploration.

A tour of the Musanze Caves involves navigating various smaller chambers. Armed with helmets and flashlights, the group descended steep stone stairs into echoey caverns. Some caves were bordered by vegetation while others had massive holes in their ceilings, giving off a mystical effect as sunlight poured onto small patches of greenery. After spending a few minutes in each cave, we would climb another set of stairs to the top then repeat the process.

Despite the midday heat already in full swing, the caves were quite cool and silent, a relaxing escape from the world above us.

After lunch at a local restaurant, the delegations set off on the bus again for our second activity of the day: a visit to The Ellen DeGeneres Campus of the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund. Best known for her conservation efforts and research on mountain gorillas, primatologist Dian Fossey dedicated her life to fighting poachers and more deeply understanding the species. In wake of her work, researchers and conservationists alike created the Fossey Fund 55 years ago to help preserve wild gorilla populations and support the communities that share their forest homes. In 2018, the Fossey Fund received a lead gift from Ellen DeGeneres and her wife, allowing the fund to create a purpose-built facility aimed at accelerating science and conservation work. Since then thousands of donors have supported the project and helped create a research and learning facility.

Once on campus, our group had the opportunity to read and watch films about gorillas past and present who had been cared for by the fund. Some students had the opportunity to participate in a virtual reality fixture created by the facility which allowed them to interact one-on-one with gorillas currently living in forest families.

Alongside another student delegate, Fernanda Paz ’25 virtually interacts with a gorilla family that is taken care of and studied by the Dian Fossey Fund. Through donations made by several families and individuals, the construction of the facility and installation of high tech features were made possible. While wearing the goggles, Fernanda was actually able to interact with the gorillas, with small babies even climbing into her lap.

After a quick visit to the campus’ café and gift shop, we took a bus ride to Rwanda’s Gorilla Guardians Village, which is operated by former poachers who now make a living via performances and cultural demonstrations to those who visit. Students and chaperones enjoyed welcoming dance and music before they were given the opportunity to shoot a bow and arrow, ground flour, and dress as tribespeople.

After witnessing a traditional wedding ceremony take place in the village, the group finally boarded the bus for a three-hour drive back to Kigali after a long day full of adventure, learning, and exploration. Back at the hotel, Hackley delegates enjoyed another meal of popcorn chicken and fries before turning in for the night.

The next morning, both delegations reunited on the bus along with students from Green Hills Academy, a Round Square affiliated school located in Kigali. After starting the day with a two-hour walk through the city, stopping at vendors and viewing points along the way, the group visited the Kigali Genocide Memorial.

Convention holds that the Hutus are a Bantu people who first settled in Rwanda. The Tutsis are a Nilotic people who migrated from the north and east. In time however, Hutus and Tutsis spoke the same language, followed the same religion, intermarried, and lived intermingled. Because of such integration, Hutus and Tutsis could at best have been distinguished as vague ethnic groups. That is, until Europeans arrived in Rwanda at the end of the nineteenth century. They formed a picture of a distinguished race of warrior kings, the Tutsis, surrounded by a subordinate race of short, darker peasants, the Hutus.

At the time, Africa had been opened up to Europeans through the imaginations of explorers and empires that wished to conquer its land and people. By 1897, Germany set up its first administrative offices in the country and instituted a policy of indirect rule. Tutsi elites exploited the protection and license extended by Germans to pursue internal feuds and further superiority over Hutus.

Decades later, the League of Nations turned Rwanda over to Belgium as a spoil of World War I, and by this time the Hutus and Tutsis had become clearly defined as opposing “ethnic” identities. Upon arrival, the Belgians made this polarization the main fixture of their colonial policy. Seeking out the features of the existing civilization that fit their own ideas of subjugation, the Belgians bent those features to fit their agenda. Dispatching scientists to Rwanda, the colonizers concluded that Tutsis had “nobler” more “naturally” aristocratic features than the “bestial” Hutus.

Through the disenfranchisement of Hutus, Tutsi elites were given nearly unlimited power to exploit labor and levy taxes. Identity cards were created to further isolate the two groups from one another and the Belgian regime of forced labor made Hutu suffering a requirement while Tutsis were placed over them as taskmasters. “Ethnicity” became the defining feature of Rwandan existence.

Hutu political activists started calling for majority rule and a social revolution. Political struggle was not for equality but rather for the group that could ethnically dominate the other. In 1957, a group of nine Hutu intellectuals published a statement known as the Hutu Manifesto, which argued that the Tutsis were foreign invaders and that Rwanda was by rights a nation of the Hutu majority. Tension and conflict mounted and came to a head in 1994 when bands of Hutus attacked Tutsi authorities and burnt their homes to the ground.

Violence began in Kigali and spread throughout most of the country. Hutu neighbors, friends, and spouses turned on their Tutsi counterparts, taking part in a horrific genocide that lasted months until July of that year.

After having closely studied the Rwandan Genocide in 20th Century History during my junior year, visiting the memorial made the experience especially significant. With an understanding of the genocide based on broader themes of colonization, I went into the memorial with the goal of more deeply reflecting on the personal stories and experiences of those who survived.

Visiting the site was an incredibly emotional experience that emphasized the importance of an inclusive curriculum that integrates accurate history and sheds light on the role of harmful rhetoric in global tragedy.

The opportunity to visit Rwanda was a unique one as the country is still rebuilding in a post-genocide era. Even though visiting the Gorilla Guardians Village and the Musanze Caves was strong evidence of the people’s lasting appreciation for their cultural heritage, ethnic identity is very much an avoided topic of conversation. Though the distinction between Hutu and Tutsi identities still exists, it would be inappropriate to inquire about which group a person belongs to.

The level of tragedy experienced by the people seems to be an avoided topic, possibly out of fear that tensions might grow again. Even Green Hills Academy students shared that they had never visited the Genocide Memorial despite the school only being located a short twenty minutes away.

Despite the aim of the overall trip being the conference itself, visiting Rwanda was an essential experience that I carried with me in discussion and perspective while interacting with students from all over the world.

Ms. Maddox • Nov 9, 2023 at 5:57 pm

Charlotte-this is awesome!!