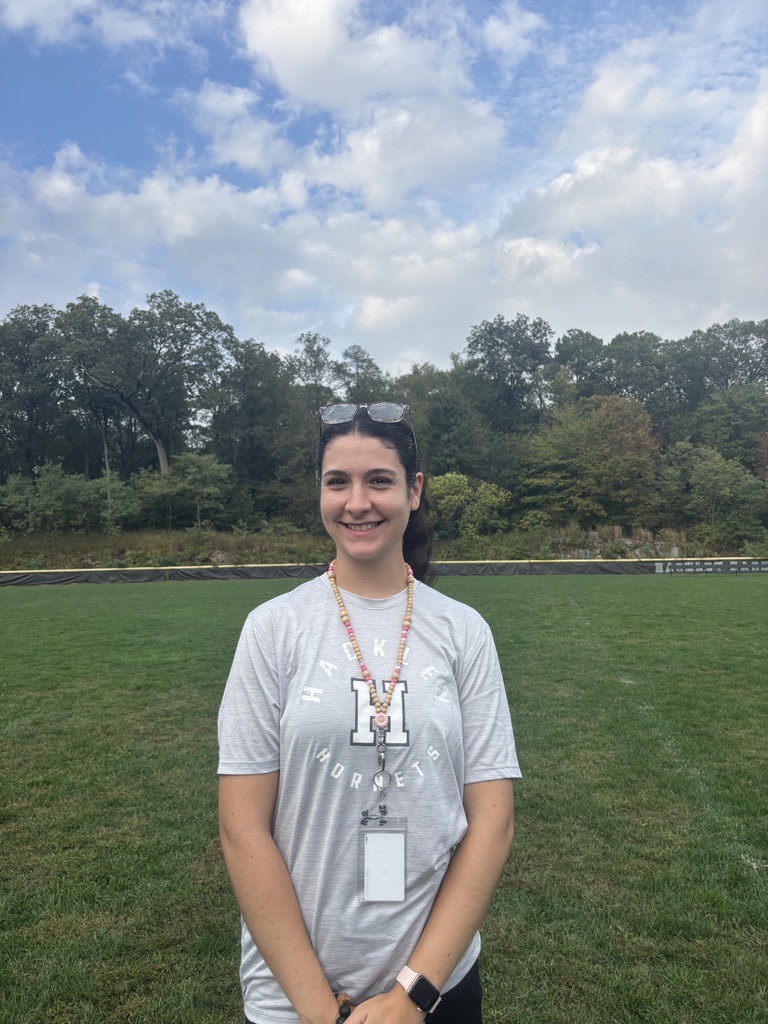

Imagine spending your whole life doing your favorite activity. As you continue to participate in this activity, you start to notice that no one around you looks like you or shares your experiences. This is exactly what happened for Mardi Fuller ‘97.

Ever since childhood, Ms. Fuller has always loved nature. It helps her feel grounded and at peace with herself. However, she started to notice that while exploring nature, she was mostly surrounded by white people. Ms. Fuller wanted to do something to change this.

Ms. Fuller started her presentation by showing images from her time at Hackley. She talked about her experiences after her time on the Hilltop, and how she eventually started to work with non-profit organizations. Ms. Fuller starred in a mini documentary called Mardi and the Whites that highlights her experience being a Black woman in the White Mountains.

Mardi Fuller recently came back to the Hilltop to deliver a presentation to upper school students and faculty about her work as an advocate for racial equity in nature. As a welcome back to campus, she was given a tour and had the opportunity to sit in an eleventh-grade English class and participate in a discussion. After her presentation, students were invited to attend a roundtable discussion if they had further questions.

Her presentation was given as part of the Szabo Lecture series, named after science teachers Kathy and Paul (“Doc”) Szabo. Following their retirement from Hackley, friends of the Szabos’s endowed a fund to host an annual science related lecture that honors their tradition of inspirational teaching and dedication to science. Before Mardi’s visit, other lectures included the Genome Project, sharks, and the Hubble Telescope. Doc Szabo started teaching at Hackley in 1963, retiring in 1996 as an Upper school science teacher. He was known for combining science with “groan-inducing humor.” While he mainly taught chemistry, he also taught math, physics, Latin, and German. He was also chairman of the Humanities department, dean of the honors program, and Upper School Director.

At the beginning of her talk, Ms. Fuller started off by talking about her experiences at Hackley. She showed some images of her time here and talked about the encouragement of Ms. Szabo, as well as Ms. Kaplan, the current head of the mathematics department. One of the most impactful classes she took here was Composition, a now-discontinued class where students used to free-write for an hour every Monday afternoon. This class helped to build the writing skills she uses today. She also cherishes the connections and networking she is able to take advantage of being a Hackley alumnus.

As Ms. Fuller said, being at Hackley shaped her thinking. She arrived at Hackley as a ninth grader, and one of the main topics she remembered learning was grammar, and reading the Bible as literature, which helped her separate some of her ideas from the Evangelical household she was raised in.

At the start of her career, Ms. Fuller worked in a more corporate setting. Slowly, she decided to move into the nonprofit sector, as she wanted to use her skills to impact social change. She works part-time as a communications director for the Boston Public Schools.

Ms. Fuller has her parents to thank for her love of nature. Ever since she was a child, she has been hiking and enjoying the outdoors.

One of Ms. Fuller’s most extraordinary accomplishments was being the first Black person to hike all 48 of New Hampshire’s high peaks during the winter. A short documentary, “Mardi and the Whites,” was created to celebrate this achievement where Ms. Fuller talked about her experience hiking in the White Mountains, where she was often the only Black person there, and about colonialism and Black liberation in nature. The White Mountains are particularly special to Ms. Fuller because she finds them especially beautiful and they are close to Boston, where she lives.

“It’s like [the Adirondacks] but there’s more exposed, above treeline area where you just have a view, 360 degrees, stunning. They’re daunting mountains,” said Ms. Fuller.

Ms. Fuller had been climbing the White Mountains during winter for multiple years without having the goal of being the first Black person to climb these mountains during the winter. Once she got close to achieving this goal, a lot more planning was required of the hikes, as the weather could be extremely dangerous.

“When I got close to completing them, that’s when I realized no other Black people had done it and I just wanted a Black name on the list. Literally the reason why,” Ms. Fuller said.

After completing this feat, Ms. Fuller was happy, as she was able to inspire and pique the interest of other Black folk who may want to connect with nature in a similar way.

“I felt so wonderful. I’m not someone who wanted to check peaks off a list and say I accomplished and conquered something. But I did like the idea of getting to know the region and the mountains really well, exploring and familiarizing myself with them,” said Ms. Fuller.

This accomplishment is only one part of the work that she has done in leading events to bring others outdoors into the mountains and be connected with their community and preservation efforts within them.

Another important topic Ms. Fuller discussed in “Mardi and the Whites” was the idea of colonialism in the outdoors.

“So a colonial mindset and approach to understanding our relationship as people to the land has been one of extraction and commodification, saying that the land is a resource, and I’m going to use that resource for my benefit as a person. And of course, that serves us in some ways, right? Drinking water and we cut down trees and make paper whatever it is a zillion things. But then that also leads to environmental degradation when we overuse and when we try to profit off the land,” said Ms. Fuller.

In order to unlearn this colonial mindset, which Ms. Fuller referred to in her speech as the White Environmental Ideology, she is learning how to adopt indigenous practices that reflect a mindset of reciprocity with the land, rather than conquering the land as one’s own.

Additionally, one of the most important parts of Ms. Fuller’s work surrounds the idea that people of color connecting with nature is an act of resistance and reclamation.

“People of color have never had freedom of movement on this land. So this is a country predicated on the idea of freedom as our premier tenant and value. We’re free. We’re a democracy. We vote for our laws and policies. But people of color have always been controlled. You’ve either been exploited through slavery, you’ve been forcibly removed – indigenous people were moved from their homelands and onto reservations or killed. We’ve never been free,” said Ms. Fuller. When white colonists settled in the United States, they took the land as theirs, even though others were on the land already and had their own practices with the land. Ms. Fuller emphasizes that people of color have contributed to agriculture, and have explored and navigated, but their stories have not been told until recently.

After the end of Ms. Fuller’s presentation, senior Cassandra Stand ran a Q&A for Ms. Fuller. Students were able to ask Ms. Fuller any remaining questions they had about her presentation. If students still had questions for Ms. Fuller, they had the opportunity to attend a Roundtable during lunch later that day.

“We have been told – people of color – that your voices don’t matter. Your contributions don’t matter. And so, me stepping into liberation and reclaiming is me saying, oh, that’s not true. That’s a lie. I get to participate just as much as the white settlers and their descendants get to participate. We’re all meant to contribute together and have our contributions equally measured. And I just get to be free and be myself and have joy and have purpose and be fully human,” said Ms. Fuller.

The journey of Ms. Fuller’s work has not been easy given the barriers that Black people have with access to nature and the outdoors. Although Ms. Fuller first thought that Black people weren’t going outdoors because they simply had not had as many opportunities to get out into nature, she realized the causes were actually more systematic.

“What [the White Environmental Ideology] led to was all sorts of barriers for Black people and people of color feeling as though they belong, feeling as though they have a place. And also real-life, tangible structural barriers like desegregation…If you have been cut off from that access, you’re not going to, over generations, develop that continuity of like, ‘My grandparents took me camping’ or ‘I went hiking with my aunties or my parents’ or whatever it is. If you don’t build that, you don’t have that history, then it’s just not in your culture,” Ms. Fuller said. She also expressed that white people are often unaware of barriers like these, as they have never thought about why activities like hiking and camping might be big in their culture. Ms. Fuller also explained how sometimes in Black communities these barriers with nature are not recognized because they have not been thought about. But to Ms. Fuller, reconnecting with nature is extremely crucial and may not look like hiking, but instead taking a walk or sitting at the beach and observing the ocean.

In all of this work, one of the most surprising things to Ms. Fuller is how much joy those who she works with get out of small things in nature. Even if she plans to take out a group at a time when the weather is not going to be great and views might be smaller, she can still have great experiences.

“One day, in this exact scenario where it was cloudy out, I had taken a group up. And okay, I have these dreadlocks. Someone else had a big afro – two people had big afros. And this is the thing like all these ice crystals started to form on our hair in cool ways. And it just became like, we were just in such awe of that. We were like, ‘This is so cool, look at this!” And the way it forms on our hair. It just really looks awesome, right? So it was just so much fun. And this is like one of the best photos I’ve ever taken,” said Ms. Fuller.

To any Hackley students, especially ones that may be struggling to see themselves in places they love, Ms. Fuller says, “Use the skills that you are gaining here and the network that you have here and the support that you have here to be courageous and step into what you know, which is that you do have power and value and you deserve to feel belonging and to help create those spaces where you belong. And find the like-minded people and bring them around you and create a space that you want to be a part of.”