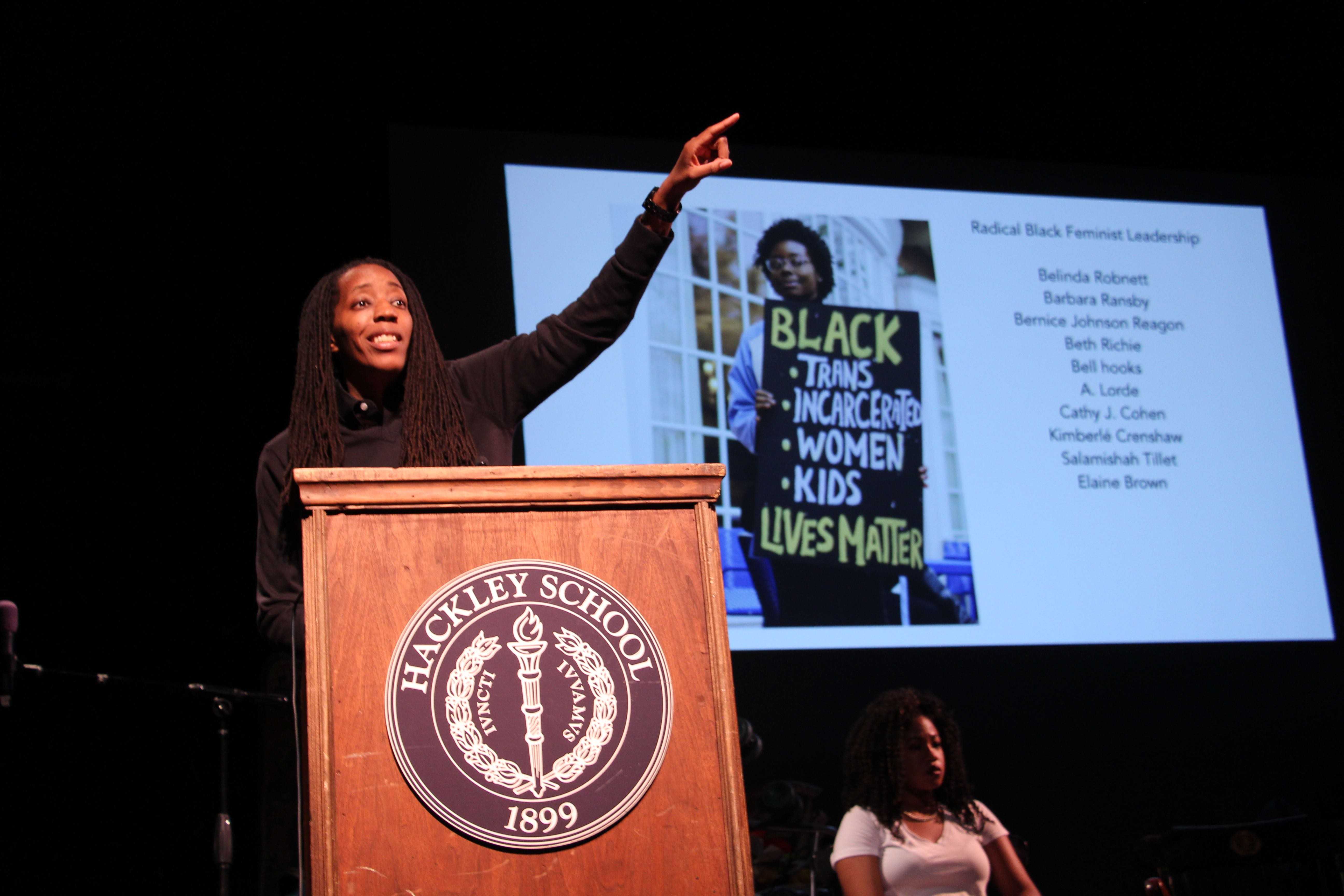

The Dial sat down with Dr. Bettina Love, Hackley’s DuBois Institute Lecturer, in an exclusive interview with juniors Benjy Renton and Roya Wolfe, in which she discussed her passion for social justice, education, hip-hop, and more.

Q: What sparked your passion to be an educator?

A: You hear many educators say, “My mom was an educator, my father was an educator;” that is not the case for me. I’m a first-generation college student. I’ve always had a special way to interact with young kids, mostly through sports. I was a high school and college basketball player, and I always thought I would be a basketball coach. In my junior year of college, I took a class in education out of nowhere, and that was the spark. When I started to learn more about education and the issues impacting minority kids and marginalized kids in education, that was when I said that I want to be a teacher. When I realized that I could take my passion for sports and pour it into being a teacher, that was where the spark came from.

Q: How have you been able to implement your research into the curriculum at the Kindezi schools?

A: Kindezi is my testing ground. It really helps to be a researcher, educator and the chair of a charter school. In Kindezi’s third year, I created a class called “Real Talk: Hip Hop Education for Social Justice,” and that is where I try to take my research looking at hip hop-based education and figure some things out. If you look at hip hop-based education, you’ll see that it’s really focused (until I came along) on high school students. Coming from an early childhood education background, I’m thinking to myself, “High school is great. But what if we can get them thinking about hip hop, rhymes and movement in 2nd grade? How about using DJing to tell stories and as an art form to understand literature?” I started thinking about art and graffiti. Art is such an important part of hip hop. I worked on how we could take the culture and traditions of hip hop and implement that into early childhood classrooms. Being embedded in a charter school allowed me to have that hip hop class. Then, I started to document that. I started to videotape everything I did with my kids and write lesson plans for teachers to show them you can talk about issues for social justice and hip hop in elementary school.

Q: What has been your most inspiring (or favorite) moment as a teacher?

A: The first thing that comes to mind is that I taught at a tough school in the Miami area. I was a first-year teacher, and I just started bringing hip hop into the classroom. I had to because the school that I taught at was 30% African American, 30% Latino and another 30% Haitian. What was going to get us all together? I just wanted to try hip hop. At that moment, that was the light. About 2 weeks into me coming up with a hip hop unit and changing everything around in the classroom, I drove into school in my maroon Ford Explorer truck, and there were 10 kids outside waiting for me. They said “Let’s go!” And that’s when I saw that this works. They’re waiting for me. They’re getting my bag out of my truck. At that moment, I didn’t know what I was doing, but I knew I was doing something right. And that was one of my proudest moments. It got the kids engaged in school — learning, thinking, debating, arguing. And I realized that it was something that I wanted to pursue. That experience drew me out of teaching to get a PhD and think about this on a larger scale than just in my classroom.

Q: What brought you out of the elementary school classroom and into a research career and PhD program?

A: It was my experiences in Miami teaching those kids. I always had this desire to use hip hop — it’s who I am, it’s part of my culture. So I always wanted to bring that in but I didn’t know how. I grew up listening to hip hop, and it was not only a musical genre that I loved but it was where the stories about my community were being told when no one in the school building would tell those stories to us. No one in the school building told us our history, that wasn’t in our schools. That for me is where I learned what it meant to be a black kid, an urban kid, a kid from the African diaspora. I learned all of that early on in my life through hip hop and programs outside of the school building. For me, I wanted to bring what I’ve learned outside of school (that was so important to me) back into school. I’m somebody who deeply believes that you have a formal education and an informal education. Both of those educations are extremely important.

Q: How have current events involving race relations and racism such as incidents with police brutality, Beyoncé’s “Formation” music video, and even Kendrick Lamar’s Grammy performance affected your experiences in the classroom environment?

A: I think they’re difficult because you want to teach kids about these situations, and you want them to be aware of them. You want them to understand the decay of urban cities and why urban cities look the way they look. You want them to understand how policing has changed over time — policing wasn’t always like this. You want them to understand it’s not that folks in these communities don’t want police, they want better police. But you also have to at a certain point step back and say I’m teaching you about this, but this could also be me. I think that’s the hardest part for me is that I’m teaching you about Sandra Bland, but I am Sandra Bland, and that’s a very difficult part that I don’t think every educator has to think about as they teach kids about this. I’m teaching you about it, but I’m also living it every day. I live in Atlanta Georgia, but I work at the University of Georgia, which is ninety minutes away. I have a ninety minute drive through the backwoods of Georgia to get to work I am Sandra Bland. If I get pulled over? I am Sandra Bland. It’s a very emotional period right now, not only to teach it, but to live it.

Q: How do you envision a movement for social change through connection to cultures spreading to communities such as Hackley?

A: I think the great thing about what you’re seeing now, particularly with movements like the Black Lives Matter movement, is that it is a decentralized movement with multiple leaders who are invested in sustainable change. They’re not invested in platitudes, photoshoots, one-liners that get you on TV, these individuals are ready for sustainable change. I think deeply about this, that they understand what happened in the past. They’ve studied black movements. These young kids of 19 and 20 years old understand that if you take out one leader, there is no movement anymore. And we saw that with King. Who do you turn to? Who is the leader? No one can tell you right now who can sit at that table and say “We speak for Black Lives Matter.” No one can do that. At a certain point, that’s a weakness, but that’s also a huge strength. No matter what happens, this movement must go on, and I think that these young kids are not perfect, but they’re learning from their mistakes quickly. And they’re learning from their mistakes from the past even quicker. I think you’ll see that they’ll make incredible changes. Already, Black Lives Matter movement is no more than two years old, and look at the strides they’ve made. We’re talking about 26 chapters in the United States already. They are credited for almost 46 different gun laws and investigations. In my home state Georgia right now, Rise Up Georgia has been instrumental in these types of ideas and laws. That’s big. Not only they going after police brutality, they’re going after the structure. We’re not just going after the cop, we’re going after the structure that keeps these cops in these places of power. We need to understand this structure and make structural changes. They want a total revisioning of justice, and that’s what I think makes this an unbelievable movement

Q: How do you see hip hop and alternative education sparking a movement for inclusion and justice?

A: Hip Hop has always done that. From the very beginning of hip hop, it has always been about inclusion. If you look at the early phases of hip hop, it was everybody. It wasn’t just black kids, it was white kids, it was Latino kids, it was everybody. When you move out of corporate America hip hop and you understand what I like to call “the DIY of underground hip hop.” Hip hop has always been underground and speaks back to resistance. Hip hop since its conception has always been a way for young people to deal with trauma and struggle, and to find ways to resist, tell new stories and speak back. Hip hop and the arts have always (and will always) be a part of any social movement. I think sometimes we forget that you can’t but the music before the movement. That’s why you see Beyoncé and Kendrick Lamar responding to the movement. It’s an artist’s job to respond to its people who are listening to you. To relate to the everyday things that are going on in your community. Nina Simone said it best. And so you’re seeing these people do their jobs. And they’re doing it well. They’re doing it ways in which we’ve never seen before. It’s witnessing the trauma, but also the joy of trauma. People forget that slaves danced, slaves loved, slaves founded jazz. There’s no way around it, that as much resistance and trauma that black folks in this country have experienced, they meet that trauma with the same amount of resistance and joy from that resistance. Beyoncé is talking about what it means to be here as an African American. And that’s a very complex thing which he understands. With Kendrick’s performance at the Grammys, he’s calling on his ancestors to guide him. And that’s what artists do. I think we’re seeing something similar to Drake’s album What a Time To Be Alive. I think we’re thinking about revolution differently than we’ve ever thought about it before. You also see queer bodies in the forefront of the Beyoncé video. We don’t see that particularly in hip hop. And so to have that distinctive New Orleans voice is powerful in that video. That video was as black and as southern as it could be, which is the heart of blackness. Particularly for African American culture, we all in some particular way come through the South.

Q: What are you looking forward to achieving with your fellowship at Harvard?

A: I’m working on a curriculum called “Get Free: Hip Hop Civics Education.” In the last six months, I’ve been going around talking to some of the top young activists in the county and getting their stories on tape, and then taking those video clips and links to build questions and curriculum on a website. Young kids in middle and high school can go and learn about activists from their city. I’ve done about 10 cities so far, and I hope to add one or two every month until it is huge. I want kids to not only be able to go onto the website and see an activist from their city, but also to understand what’s happening in their city. You take a kid in Chicago, for instance, a city known for its high crime. But why is that? No one talks about how the poverty levels in Chicago are more deplorable than 50 years ago, when King was alive. All the things we measure success by, some of those measurements in some urban areas are deplorable. And so why is that? We have to start talking to young kids about what is happening in urban cities: the gentrification, the erosion of public services and public goods for the public, we have to start explaining to kids that this didn’t happen overnight. This is a project to take back urban communities. And so you’re watching the erosion of communities in Detroit, Atlanta, Chicago and DC. When you take somebody’s base away, where are you going to get it? Chicago has some of the first housing projects in the country — 1,000 apartments in one housing complex. If you tear it down, where do those people go? If you close schools, where do these people go? You’re taking the infrastructure. You just don’t bounce back from that. And you just want residents to do what? I think kids have to understand that. And nobody can explain that better than activists. There’s also the ingenuity and creativity of hip hop to inspire these young folks. I’m currently working on the curriculum and a book proposal to write a book about why this new type of Civics Ed (pushing and extending our definitions of democracy, citizenship and community) works. And you have many kids who are pushed out of schools but now are protesting. Why is that? They’re mad. They’re upset. They don’t want the same fate for other kids. You’re seeing kids push civic education. You’re seeing kids develop an understanding of how to make this world better. But they’re not getting that inside schools. They’re getting that in the streets. And that needs to be honored.

Photos by Benjy Renton and Roya Wolfe.

Dr. Bettina Love on new “Get Free” Curriculum from Hackley Dial on Vimeo.

Interview by Benjy Renton and Roya Wolfe.

![Although the affect of COVID-19 has been on a decline with less cases and deaths allowing most of us to remain mask free, people on the Hilltop are still choosing to mask up. Personal health concerns as well as helping an elderly neighbor are reasons as to why middle school science teacher Emma Olsen still wears a mask years after the COVID-19 pandemic began. Since I am helping take care of him, you know I go over to work with his dogs, that kind of thing; I dont want to bring [the virus] home to him, Ms. Olsen said.](https://hsdial.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IMG_1713-900x1200.jpg)