The Electoral College: an outdated system

Credit: Benjy Renton

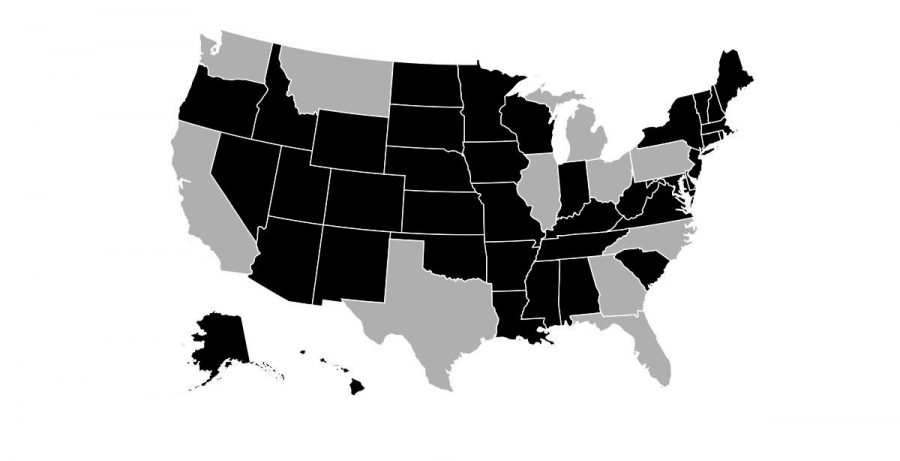

By winning 51% of the shaded states, a candidate can still gain the Electoral College majority with only 22% of the popular vote.

December 17, 2016

When the Constitution was written and ratified in the 18th century, the election of the office of President of the United States was intentionally removed from the will of the people, so as to protect the interests of the elite. However, following the presidency of Andrew Jackson, the American people have grown to understand that ours is a more democratic and representative government, whose leader ought to gain power by the will of the people.

The Electoral College has retained the method of choosing the executive office every four years, but not many are well-acquainted with this system. It includes 538 electors, who are selected by each state’s legislature and equal to that state’s combined number of representatives and senators. By convention, they have typically followed the will of their state in their choice, but are not bound to such by any federal law. Whichever candidate gains the ballot of at least 270 of these electors, more than half, wins the presidency. This system, riddled with many flaws, has the ultimate effect of denying true representation.

The Electoral College inherently gives certain states, particularly those with smaller populations, more votes per person than those with larger populations. This results in a situation where a vote from a citizen of the populous state of California is worth far less than that of the less populated state of Montana. A dynamic is thereby created where votes are distributed unevenly, with some people’s voices seen to count more than others. This directly contradicts the ideals of equality and liberty upon which America was founded.

Furthermore, almost all states utilize a winner-take-all system, in which whichever candidate wins more than 50% of the vote gains all that state’s electoral vote. This could swing an election in favor of a candidate who does not win a majority, as they could win several states by a small margin and gain its entire population’s effective support. These two effects allow for elections to be so unfair, that hypothetically a candidate could win the presidency with as little as 22% of the popular vote, winning in states where voters are worth more, and by margins barely above 50% in each state. A government that claims to be of, for, and by the people cannot hold up such a claim if its ultimate authority can be decided by less than a quarter of its people.

Defenders of the Electoral College will argue that this inequity of electors is by design and in the interest of the nation, as it gives smaller states a larger voice, so they are not ignored. However, history shows no indication of this to be the case. On the campaign trail, presidential candidates do not spend time or money on smaller states.

In fact, most of the candidates in the past 50 years have spent upwards of 57% of their time and money campaigning in four states: Ohio, Florida, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, all of which have considerably large populations, and do not benefit from the electoral college’s voter inequity. This is owing to the aforementioned winner-take-all system, which, in the view of a candidate, renders a win in a state by 10,000 votes no more valuable than a win by ten votes. Thus, candidates spend far less time in states where they expect to have a large margin for victory, instead focusing on swing states, where either candidate may clinch a small majority.

Candidates are incentivised to ignore other state’s issues, both small and large for the sake of battleground states, harming the nation as a whole. If the Electoral College was designed to protect the interests of smaller states and prevent the oppression of larger ones, it is failing drastically. The Electoral College is neither representative, nor in the interests of a federal system such as the U.S. All its flaws are easily rectifiable, simply by choosing our commander-in-chief by popular vote.